To often when I have the opportunity to spend time in serious conversation about martial arts, the discussion will inevitably turn to one of two subjects: how to keep the doors open and the bills paid and/or the best way to transmit our respective teachings. The discussion often breaks down along the lines of traditional vs. contemporary, and commercial vs. non-profit, with most people viewing the lines of demarcation as much more distinct than I.

Whichever camp influences our point of view, I think that we are talking about the wrong things. I believe that the answers to both questions lie in the examination of a third, that being how martial arts practitioners can best provide an antidote to the negative influences of society. Our tradition states that there are “immeasurable rewards” for those who can find their personal path through “helping their fellow man.” [1] The lives of the great masters reflect their sense of responsibility to society. Nagamine Shoshin left his career in law enforcement to live the “way” of the masters, because he believed karate could provide an antidote to the ills of war-ravaged Okinawan society. I would argue that today’s moral imperatives are no less pressing, and that, as Bubishi provides a template for so many modern styles of karate-do, the principles of the Western positive psychology movement provides a road map to teaching the art successfully in our modern world.

In the early 1900s, two men a half a world apart both referred to a statement attributed to the Duke of Wellington by a French journalist in 1855: “The defeat of Napoleon began on the playing fields of Eton.” Master Itosu Anko in Okinawa and Dr. John E. Bradley in Great Britain both hailed the educational and character building values of stringent physical education. Master Itosu’s reference to Wellington in his 1908 letter, “Ten lessons of To-Te,” is relatively well known in martial arts circles. Less well known is Bradley’s 1902 article, “The Educational Value of Play,” published in The Review of Education. In his article, Bradley quotes Wellington watching a football game at Eton College and stating, “There’s where the battle of Waterloo was won.” Bradley writes “Play is a preparation for work. It soon ceases to satisfy unless it involves an end to be attained---unless, in a way, it becomes work; and it is no less true that work, in order to be at its best, must have in it some of the charm of play, it is not easy to sharply distinguish play from work.” [2] Bradley’s writings suggested he believed that there was something more. He believed that the Duke of Wellington was talking about more than war, that the Eton games were about life as well as death.

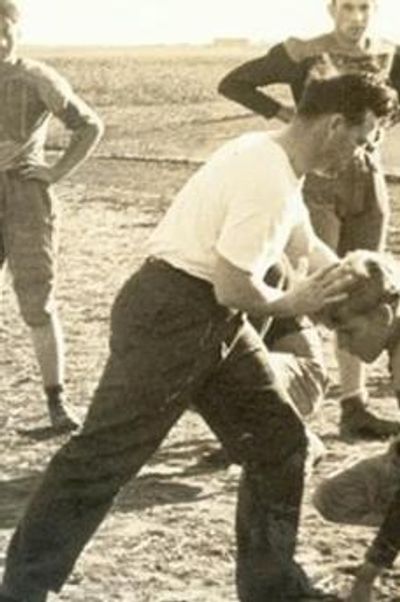

Coach Ken Corcoran with Boys Town football team, 1930s, Omaha,

Nebraska. Corcoran coached football, basketball, baseball, and

boxingat Boys Town from 1935 to 1942. His football team earned

a national reputation in less than a decade and helped spread Father

Flanagan's message that "There are no bad boys. There is only bad

environment, bad training, bad example, bad thinking."In the 1940s

at Boys Town outside of Omaha Nebraska, in United States, an Irish

priest Father Flanagan was putting such theories to an innovative test.

Literally a social experiment built from the ground up. He believed

,”There are no bad boys. There is only bad environment, bad training,

bad example, bad thinking.” [3] With no tradition, nothing more than

old farm, and in the beginning almost no money he built a town for the

development of boys. He built the town a round hard work and

opportunity. A cornerstone in his programming was his sports program

which included football basketball baseball track and boxing. His protégé, the then nationally famous coach Kenneth Corcoran echoed Wellington, Bradley, and Itosu in his sentiments on sport. Writing in the boy’s town paper, he suggested that people worried about the condition of the Army for wartime activities should consider that “hard work combined with definite exercise in play seemed to be the answer.” [4] In short, he put forth the same argument as Itsou, that properly done, sports would help the participants to prepare for the Army. Though these statements were made in the context of war, an examination of all four men's lives will quickly suggest that they expected more from their respective athletes than that they be prepared for war. Their expectations are reflected in the Okinawan meaning of Bushi, an individual who is respected not only for physical prowess, but also “for being a civilized, principled gentleman.” [5] (Goodwin paraphrasing Katsuhiko Shinzato) Even the Okinawan King’s own guard were not given the honorific title of Bushi, but were instead referred to as Samurais, or warriors. (Goodwin)

Similar concepts formed the foundation of Father Flanagan’s Boys Town. His public speeches and writings are filled with references to building character and citizenship through hard work and goal-driven activities. At a time when “juvenile delinquents” were routinely warehoused and beaten, Flanagan was known internationally as an outspoken, innovative, and sometimes controversial advocate for children, spreading his message throughout America, Europe, and Asia.

He believed, as Master Wang, that “An idle mind is a demon’s workshop.” [6] There is a clear overlap between what Father Flanagan believed and the philosophy of Bubishi that we strive to be a “person of dignified behavior, recognized for kindness and consideration of others less fortunate.” [7]Corcoran, the author’s maternal Grandfather, and himself an orphan hired by Father Flanagan at 22, was fond of saying that foundations are built slowly through hard work. Once built, the resulting “character” is stronger than that which came about the “easy way,” which he believed produced a weak character that could “crack wide open in the first storm of life.” [8] These men were clearly architects of activities with educational expectations beyond mere physical utility. Those expectations were born out some fifty years later by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a Czechoslovakian American psychologist whose scientific study developed a framework for building on the success described by Bradley, demonstrated by Father Flanagan, and the expectations of Itosu outlined in his letter, “Ten Lessons of To-Te.” In the course of Itosu’s and his student’s lives, Okinawa underwent a whirlwind of change. One of those students at the forefront of responding to that change was Gichin Funakoshi. He listed as one of his principles "when you step beyond your own gate, you face a million enemies." I am sure he and his contemporaries would see it no different today. We live in an increasingly frightening world. People fear for their safety and their children’s safety, and worry about what kind of people their children will become. They worry about the character of their children. They are concerned about bad influences and the lack of good examples. Martial arts instructors who can help with these concerns will likely have no problem with the quality or quantity of their students.

The debate of how to approach teaching, transmission, and the continuation of the martial arts is nothing new. Even among the students of the strongest masters, there have often been differing interpretations of their instructors’ work and intent. In the U.S., with our special brand of independence and dismissive tendencies, these attitudes can be taken to the extreme. These differences have at times acted like an accelerant to a restorative prairie grass burn or sometimes out-and-out arson, depending upon your point of view.

Most people I come in contact with in the martial arts world see me as a traditionalist, while a minority of “truly” traditional practitioners, whose opinions I otherwise value, take exception with my teaching methods and cast me as a contemporary instructor. One can gain a lot of perspective from this “neither fish nor fowl” vantage point. I see myself as utilizing flexibility in my teaching to respond to the needs of society, based upon sound traditional teachings combined with modern scientific study.

Funakoshi spoke of such flexibility in training for people who were physically or spiritually weak. He also said that karate fostered “the traits of courage, courtesy, integrity, humility, and self control in those who have found its essence,” characteristics that are often considered in all too short supply today. Yet, all too often, such flexibility in teaching is viewed as a weakness on the part of the instructor or any school of thought that incorporates this approach. But if we are charged with creating an environment where students can foster the characteristics that Funakoshi spoke of, then this approach should be seen as tactical rather than indulgent.

The phenomenon of contemporary entrenchment among some practitioners since World War II, in contrast to our true tradition of adaptation in response to societal needs, is particularly deplorable given the circumstances of modern society. Our children are growing up in communities in which they are feeling increasingly isolated. They cling to their peers in a sea of instability due to the mobility of our society. In addition, they are living in communities with a growing acceptance of illicit drugs and increasing tolerance for exposure to violence and crime. Many children are also growing up in dysfunctional families without the benefit of any form of extended family. Increasing numbers of children are experiencing violence in their own homes, often at the hands of stepparents or family friends.

When these children leave their homes, they go off to schools which are often disorganized, failing academically, and in general suffering from the overall community’s lack of interest in their success. In schools and elsewhere, they are undoubtedly exposed to a rising number of children who participate in risk-taking and myriad acts of antisocial behavior. [9] The behaviors travel the continuum from intimidation, stealing, and experimentation with drugs, alcohol, and sex to school delinquency, tardiness, and illiteracy--all problems, which if not faced, will plague them into adulthood.

One among many recent examples is a subway assault in New York by a group of teenage girls who taunted, threatened, and eventually beat a man as the train moved from its station to the next stop. They did this while a reportedly unrelated teenager filmed the incident to be uploaded to You-Tube. This is a clear demonstration of individuals who believe that anti-social behavior is a means to whatever ends they are seeking, and for whom exposure is not a deterrent, but rather something to be sought.

Social scientists such as Garbarino, Polk, and Powers have concluded that the toxic environment in which young people find themselves compounds a sense of isolation and lack of empowerment that leads some children to believe that antisocial paths are the only avenues available to them. This sense of isolation reveals itself throughout the literature of the angry adolescent. Garbarino emphatically states that “BEING LEFT OUT IS POISONOUS” and reiterates that the consequences of parental or family rejection are “psychologically devastating.” [10]

Examining the recent rise in violence among middle-class youth from “good families,” he suggests that it is actually easier to recognize this “sense of alienation and disenfranchisement when it occurs among an identified minority,” but the problems are wide spread in our society. [11] He notes that “rejection is more than a family issue” and cites examples of “small town shooters” who experienced rejection at home and among their peers. [12] And like Ron Powers, Garbarino observes that these individuals are “outsiders” in their own minds and emotional experiences. [13]

The Dojo and Positive psychology offer a counterpoint to “traditional” psychology of the past 30 years, and a number of recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of karate as an intervention for anti-social behavior. For example, a 2006 study published in the International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology showed “significant improvement” among at-risk children in a 10 month karate program in “three domains of temperament---intensity, adaptability, and mood regulation.” [14] This study and others like it, demonstrate that when approached correctly, karate-do can provide an antidote to the challenges faced by society today.

Psychology born of Freudian, behavioral approaches and the modern more-martial-than-art approach to post-war Karate, have ultimately failed in dealing with the problems of our youth today. Among the myriad of different behavioral approaches is a recurrent theme of focusing on extrinsic rewards for positive behavior and consequences for breaking rules. The problem, of course, is that this approach does not always work with students who see rules broken on a regular basis in society. As a counterpoint, positive psychology studies the behavior of happy, successful individuals and demonstrates how to duplicate these behaviors, focusing on intrinsic rather than extrinsic rewards.

The research findings of “optimal experience” within the field of positive psychology can serve as a template for instructors and their students and effectively provide an outline for the best of our teachings and traditions. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (foremost authority in the field of positive psychology and Director of the Quality of Life Research Center at Claremont Graduate University) has identified the components of optimal experience, which can be utilized to develop curriculum designed to bring about a state of inclusion and empowerment. Optimal experience provides a modern scientific guide to how to achieve the goals articulated in the philosophy of the ancient texts.

In Jamie Chamberlin’s APA Monitor article on Csikszentmihalyi, “Reaching Flow to Optimize Work and Play,” Csikszentmihalyi suggests that “a typical day is full of anxiety and boredom.” [15] This is the vantage point from which far too many of our youth view their lives. Karate-do’s possibilities for inclusion and empowerment are the precise coordinates at which youth programming, prevention science, and positive psychology converge to address adolescent antisocial behavior. Likewise, positive psychology provides a roadmap by which traditional martial artists can see their way through complex, and often invisible, passages through a seemingly insurmountable set of problems.

In his book, Flow: the Psychology of Optimal Experience, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi sets forth definitive steps to achieving optimal experience, which are directly applicable to martial arts training. The steps are derived from his initial study of artists, which he later applied to athletes, artisans, and eventually the general public. Csikszentmihalyi defines “flow” or the state some might call being in “the zone” not as something that happens to us, but something we “make happen” when our “body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.” [16] He describes the state of flow as follows:

“…a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems. Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted.” [17]

The parallels to karate practice are startling. He comments that “An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult...” [18]

In his article “Making Conscious Choices at the Edge of Chaos,” Csikszentmihalyi further suggests that the way we view our personal circumstances is filtered through three prominent screens: genetic makeup, the culture in which we grow up, and a personal sense of who we are. [19] These screens or filters outline the parameters of our thinking and the actions we take.

Karate-do can effectively alter these filters to create a positive framework. In the same article, Csikszentmihalyi suggests that optimal experiences give us a sense of connecting to something larger than our selves while simultaneously enhancing our sense of self and individual well being. This transformation happens when activities focus an individual’s attentions on “what is unique about yourself and your experience” and to further “identify yourself with goals that are connected to something larger than yourself, such as the greater common good” [20] At their best, properly taught and practiced in the traditions of Bubishi, the martial arts are an outstanding vehicle to refocus an individual’s attentions in this manner. Additionally, with the assistance of the psychological principles outlined, student and teacher alike can fulfill the responsibilities and reap the rewards outlined in the text.

These are not merely theories. Programming traditional karate directly to address the problems outlined is being successfully done. One example is on Long Island were martial arts instructors Jerry Figgiani and Tony Aloe, have developed a curriculum to meet the needs of inner city youth. The program has been so successful that it has been expanded from a three-week women’s self defense course to a full black belt program in eight schools with plans for another five, as well as a child safety program. While the program takes place in schools that routinely experience lock downs, the curriculum focuses on traditional martial arts tenets couched in the more contemporary language of non-violent conflict resolution, leadership skills, and the character development that is a natural product of such programming. Community service is a key expectation of the program. Students participate in road side cleanup, collecting clothing for churches, and working in soup kitchens. Goals are set early with regard to behavior, studying, and martial arts achievement.

Aloe and Figgiani are partners in a commercial karate school on Long Island and began their successful collaboration in 1993. In 2004, they made a conscious choice to give back to their community. They implemented their collaborative curriculum in a local high school, which resulted in increased school attendance and improvement in academic studies. Their efforts gave the greater community an opportunity to demonstrate its eagerness to be supportive of such efforts. The Police Athletic League provides funding, as does the local government. Figgiani uses his own life experiences to help the students set goals. The New York Times quotes Figgiani: “We take the experiences in our lives and talk to them about how it has given us direction in our lives...It's about choices and responsibility. Words that come out of their mouths are more powerful than any punch they could ever throw.” [21] Talking with Jerry Figgiani, he told me a very poignant story illustrating the importance of direction in our lives. One evening while teaching, Figgiani observed a car pull up in front of his Dojo. The car was left running, music blaring, as a young man in street clothes entered the building. He immediately walked out onto the training floor without removing his boots. Standing in front of the instructor visibly distraught, he reached out and embraced Figgiani in a hug. He explained that if it weren't for the program, someone would have gotten hurt that night. Sometime around a year later, the same individual return to dojo and handed the Figgiani a copy of his high school equivalency and acceptance to the two-year vocational program.

Our own goals need not be as large as a dozen after-school programs for at-risk youth. They can be as simple as helping one or two or a small number of at-risk students, as many of us do, or being flexible enough to accommodate a student who might not otherwise be able to make it. Risk is all around, as Gichin Funakoshi said. Simply setting out the right example can go a long a way. This is idea behind the Karate-No! program, sponsored by the Hikari Institute, the Hawaiian non-profit group, which is also the parent organization of the Hawaii Karate Museum. Taken to an impressive level, this anti-drug and alcohol abuse program has a web site featuring statements by instructors and students and the local mayor who helps fund the program. The web site itself has links to drug and alcohol prevention programs offering an extensive list of links from the Coalition for a Drug-Free Hawaii and the State Department of Health, as well as national links such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and Partnership for a Drug-Free America.

On the web site, Charles C. Goodwin, karate-do instructor, author, and president of the Hawaii Karate Museum, explains, “Karate training is part of a healthy lifestyle in which students take responsibility for their actions….There is no room in our dojo for drug or alcohol abuse.” [22] The site is an example of utilizing modern technology to convey strongly-held convictions by those who children might look to for an example.

The NY Times article on Aloe and Figgiani’s program outlines the “immeasurable rewards” for students, community, and instructors engaged in “helping their fellow man.” (Bubishi). It is the way of our collective martial arts traditions, as the examples of Itosu Anko, Gichin Funakoshi, and Shoshin Nagamine, among many others illustrate. The western traditions of sport as demonstrated by Corcoran, Bradley, and others in many ways mirror their eastern counter parts. Their respective successes and failures are less daunting when viewed through the ever-changing and many-faceted kaleidoscope of our not-so-discordant traditions. This was the way of Master Itosu when he looked to the West for inspiration and a model for a new way of approaching the teaching of martial arts. It is the height of irony that we in the West do not examine our own traditions in the same manner.

It is only when we ignore the common ground found in Shuhari, the Japanese concept of learning and mastery, that we become rigid, locked in the teachings of the past, and unable to deal with the problems of the present. Shuhari teaches us that, while we adhere to traditional wisdom as beginners, we must break with it when necessary, particularly when new knowledge gives us a better

Copyright © 2018 Shin Gi Tai Arts - All Rights Reserved.